Ev’ry heart beats true ’neath the magenta white and blue.

⏎

Ev’ry heart beats true ’neath the magenta white and blue.

⏎

Here’s an innocuous scientific controversy. I’ve collected a number of these, imagining that maybe they could serve as practice material for making sense of ambiguity outside one’s areas of expertise. I’m not sure it’ll do any good, but it’s worth a shot. I’ll outline the issue below, and, if you like, you can try your hand at sorting it out.

I’ll hold on to my own account of looking into this for a later post, so you can do your own investigation. Likewise with references, though it pains me.

Trichromacy

Most people are trichromats. Normal color vision involves three types of cone cells in the retina, each type with a different pigment preferentially sensitive to its own range of wavelengths of light. As a shorthand we often call these ranges red, green, and blue, and the respective cones L, M, and S (for long, medium, and short wavelength).

Is trichromacy all it takes to explain color perception in humans? Surely not, since (for example) color perception also depends on spatial relationships in the field of vision, but there’s also psychophysical evidence that there’s more processing going on at a basic level. For example, people seem to see, in the phenomenological sense, red-green and blue-yellow as pairs of pure, opposing hues, at the very least as far as we don’t talk about reddish-green or yellowish-blue.

Perhaps trichromacy tells us about the inputs transformed by a neural network whose output correlates with phenomena. What can we say about that transformation? One description you’ll often see derives from the opponent process theory proposed by Ewald Hering in 1892.

Opponent process theory

The idea is that in some sense the axes of color perception aren’t RGB but rather red-green, blue-yellow, and darkness-lightness. It wasn’t obvious when it was proposed, but this is still compatible with trichromacy. The red-green coordinate comes from the difference between L and M stimulation; blue-yellow comes from S minus the sum of L and M; and lightness comes from the sum of all three.

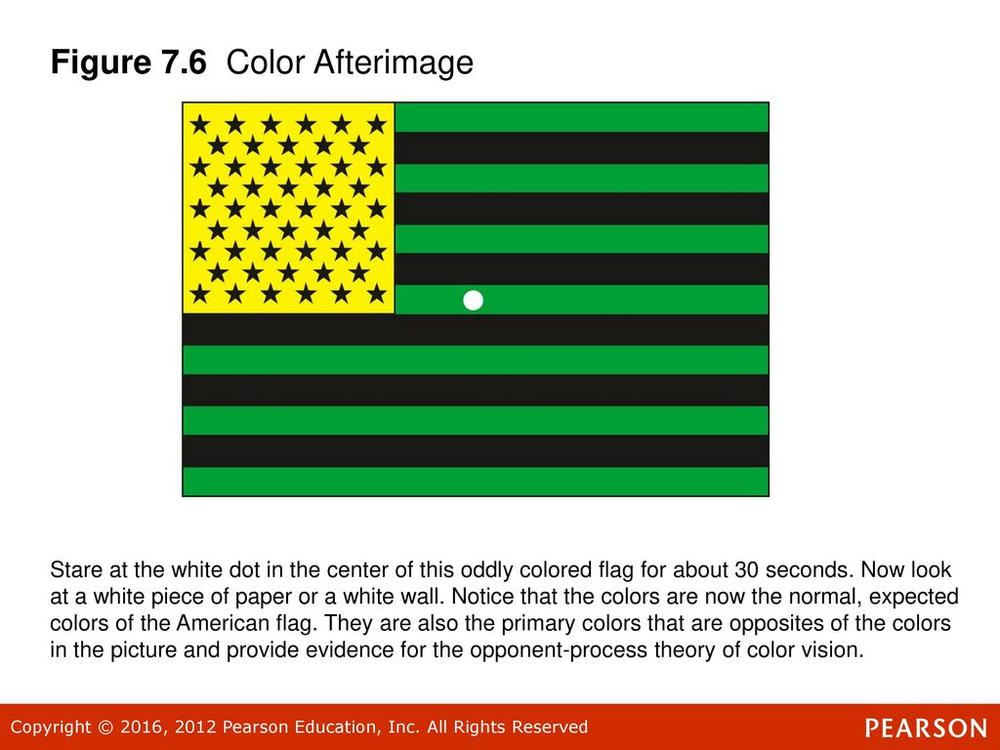

This is pretty straightforward, and it seems like something you could do with one type of neuron for each combination. International standards for color spaces use something like these opponent pairs. It explains why reddish-green and bluish-yellow are impossible colors. And maybe afterimages have something to do with fatigued opponent receptors. Plus, I saw a headline that said they found the neurons in question.

Unfortunately, the status of this theory isn’t obvious. I’ve talked to artists, teachers, interested generalists, and people working in graphic design and printing who’ve studied these topics and apply them in their work (one even writing a textbook on color). They’d generally found something they’d read about opponent process theory somewhat fishy, and on the whole they weren’t sure what to make of it.

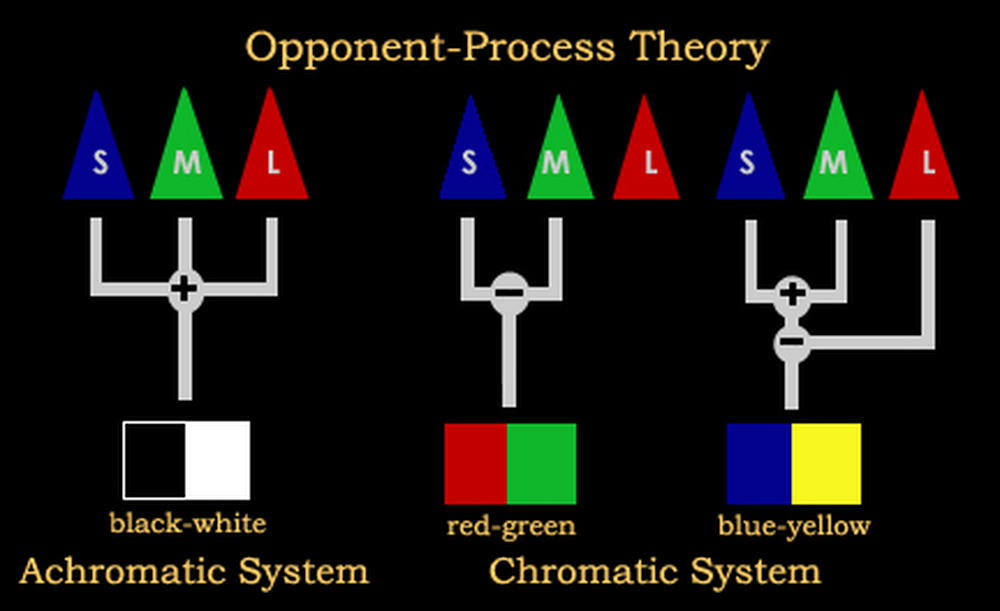

That’s entirely fair, because discussion of the theory that I’ve found in the wild—not just in blog posts, but also in scientific articles, lectures, and textbooks—repeats a number of persistent misconceptions and errors. The top Google snippet image doesn’t even illustrate the theory itself correctly!

Can you spot the error?

⏎

Can you spot the error?

⏎

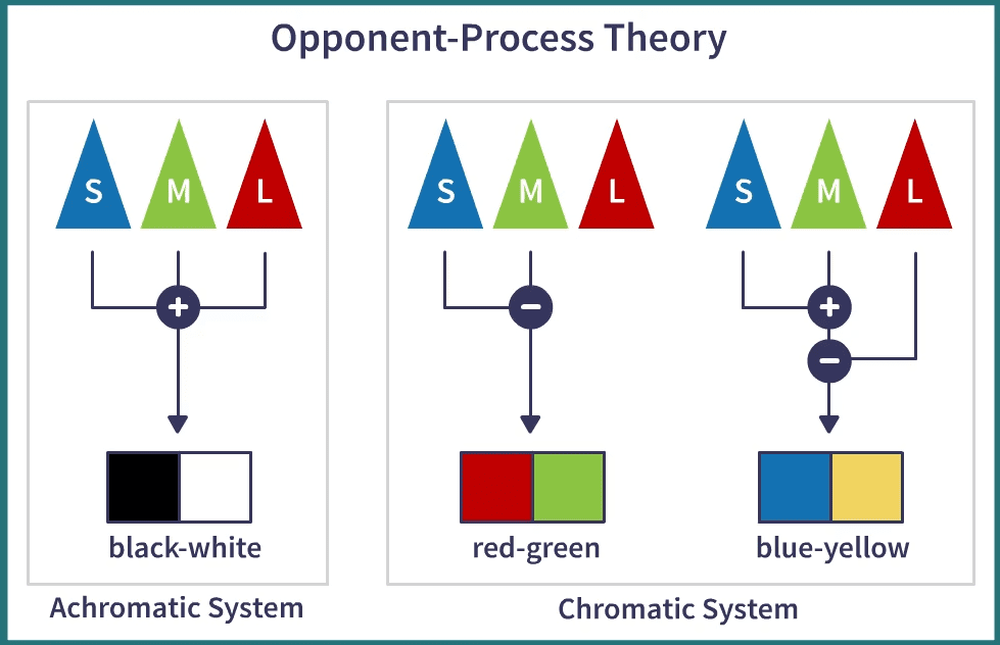

It’s even been faithfully copied.

⏎

It’s even been faithfully copied.

⏎

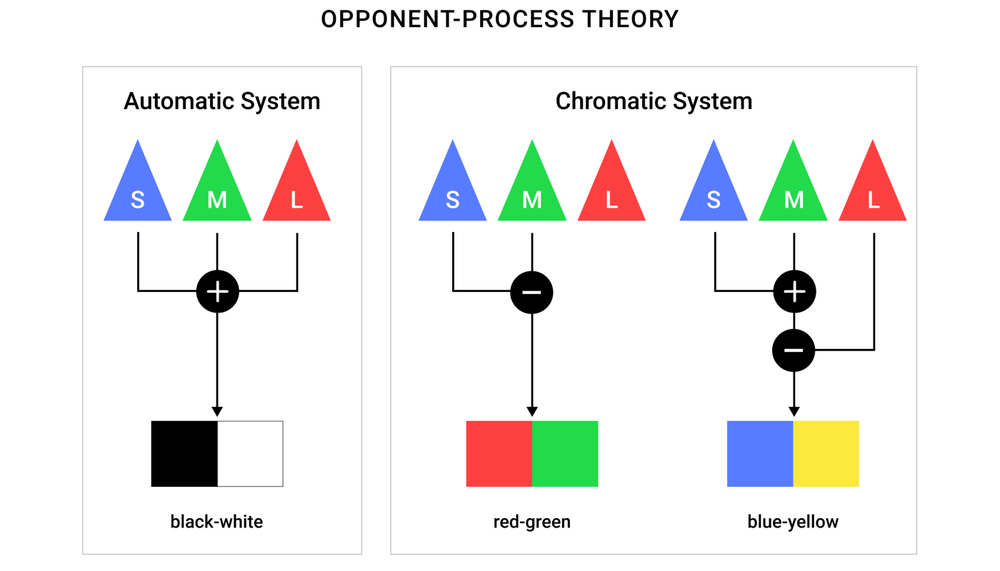

Wait—“automatic”?

⏎

Wait—“automatic”?

⏎

What’s going on here?

What is the status of opponent process theory? What scientific or philosophical questions are still live? Is the theory settled, refuted, superseded, with secondary sources and practitioners yet to catch up? How did we arrive at this situation?

What evidence does the theory explain that trichromacy doesn’t? What doesn’t it explain? What claims are misrepresentations, oversimplifications, or overreaches? What does this really have to do with afterimages, unique hues, real neurons, literal sums and differences, or color appearance models? Are you sure reddish-green is impossible and not just what we happen to name desaturated yellow instead? What would be a scrupulously correct statement of the theory?

How does one find answers to these questions? How confident should one then be?

Why do I care?

These questions are practically relevant to very few people, and certainly not to me. Light and color do interest me generally, as does experimental design in psychophysics. But I’m really interested in sensemaking. As it were. ⏎ What do you do in the face of this kind of uncertainty, where you can find authoritative voices contradicting one another? How do you deal with evidence you lack the expertise to evaluate directly? Can you get better at it? Does even trying backfire with overconfidence? ⏎

I’m thankful for many individual writers online who do this sense-making out in the open. Sometimes I wonder what could be done collectively.a a Here’s one particularly interesting project from Elizabeth of Aceso Under Glass involving others forecasting outcomes of her spot checks of various claims. ⏎ There’s no method one can follow to the letter to arrive at the correct answer—nor could there be, even in principle; this is the entire problem of science!—but we can still talk about method and give one another feedback in a live-fire environment.

The opponent process theory is relatively easy to get a handle on, I think. A few years ago someone added a section on criticism to the Wikipedia article, which made me wish I’d presented it as a puzzle sooner, but I think this could still be an interesting exercise. If you have thoughts on opponency or on the broader subject here, you can find me on Twitter or by email at the same handle @protonmail.com.