Context: I’m not a utilitarian.

This isn’t why I’m not a utilitarian—it’s just me playing with some perennial debates reappearing alongside Michael Nielsen’s notes, requests for critical writing on Effective Altruism, and prompts from Open Philanthropy. I do think utilitarians (and I’m in particular thinking of longtermist Effective Altruists) should take standard objections more seriously and be more self-skeptical in their reasoning. (I’m also not an Effective Altruist, although I support GiveWell.) This has all probably been said before.

The repugnant conclusion

The mere addition paradox is a bullet commonly bitten in utilitarian ethics. It leads to the so-called “repugnant conclusion” that a large number of lives “barely worth living” (that is, with welfare just sufficient to yield a positive contribution to the aggregate utility function) can be better than a smaller number of higher-welfare lives—that, in fact, in any given positive-utility scenario, there is always a preferable larger, lower-welfare population. This kind of utilitarianism is assumed in the discussions below.

Astronomical waste

“Astronomical waste” is a term from a short article by Nick Bostrom pointing out that not only can a spacefaring future be radically large—large enough for existential riska a that is, risk of events that preclude such a future ⏎ to dominate expected utility calculations—but also any delay in intergalactic expansion sacrifices astronomical potential utility.

Christian Tarsney observes that it might be important, against mere cubic interstellar expansion, to include a regularizing exponential decay in expected utility with time owing to a constant risk of extinction (or other event nullifying a decision’s impact on the longterm future).b b I’ve emailed the author about this, but note that the Virgo supercluster density used is too large by a factor of ten (it should be 2.9 × 10^{-10} if it hasn’t already been corrected), affecting the very long-term scenarios accordingly. ⏎ Under uncertainty, even given a small chance that nullifying events are rare enough, the next million to billion years allow existential risk reduction to outweigh near-term improvements to welfare.

Gambler’s ruin

A persistent gambler playing double or nothing will eventually go broke, even if each round has positive expected value.

Repugnant astronomical ruin

A life barely worth living is still worth living, of course, so one might object to name-calling. But the repugnance, I think, arises from the existence of a “worth living” threshold.

If the threshold is low—say, all lives today are worth living, or even all non-suicidal lives—then a superior future is full of people we would today judge to be suffering terribly. If you bite that bullet, I’m not sure how to talk to you. If the threshold is higher, then many consensually alive today don’t pass.c c Peli Grietzer has been tweeting about this. ⏎

While this is contrary to intuition, one can still bite the high-threshold bullet. But even if it’s so, the value of the longterm future now depends on establishing, as a civilization, that just “OK” (or better, as it may be) isn’t good enough. And at that point it sounds quite easy to accidentally create an astronomically bad future.

A calculation like Tarsney’s above relies on a distribution of expected utility that favors positive valence. In this case there’s good reason to expect otherwise: modern humans, at least, apparently reliably set their threshold too low.d d There are good-faith arguments that this really is true in some sense. ⏎ Moreover, a high bar makes asymmetry more plausible. As with other s-risk scenarios, you could conceivably reorient your longtermist efforts towards averting it. But even more so than with other longterm considerations, there’s a plausible argument that improving welfare today is the best way to do so.

Actually, it’s worse than that. Say our future civilization’s advanced cyberneurophilosophy gets it right, and they can accurately calculate expected utility of their own decisions. They continue to recognize that the potential utility of rapid interstellar (and, later, intergalactic) colonization dominates.

But if contemporary welfare trades off against productivity and further existential risk reduction, they’ll keep putting off prioritizing welfare indefinitely—until they meet ruin.e e Or, perhaps, now your weight on the longterm future reduces to your confidence that they correctly, collectively implement something like the Kelly criterion and balance how much present welfare they stake and how much they bank. But remember, we’re betting in pure (not log) utility, which Kelly doesn’t maximize. ⏎

A more sophisticated argument is that only once the “eschatological bound” is close enough will a surviving civilization enter the “value realization” stage, but that’s much further in the future than the epoch available to our present exponentially decaying expected utility envelope.

More technically, what I’m suggesting is to treat evaluating the longterm future as a control problem, where at any time you’re choosing between “realizing” some present value and “securing” future value. You could also model forgoing present value for faster expansion. ⏎ Say the realizable value at any time is where is civilization’s expansion speed and is the value per unit civilization volume per unit time in “realizing” mode. Alternatively, you can decline that present value and instead reduce the background existential risk per unit time from to f f In this scenario the utility cost to eliminate a fixed risk grows with the civilization size, as though that risk is eliminated by uniform policing. (If there’s a constant risk originating per-civilization-volume, and we can only reduce it, not eliminate it, then we’ll have to spend even faster than population growth on stricter policing to keep total risk constant.) ⏎

You can solve this as a Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equation by integrating backwards from the eschatological bound (or any sufficiently far-future time). More casually, you can see that the present expected value approaches in the medium term. As long as the present expected value is larger than that, you win by securing value until the instantaneously realizable value catches up, and then you start realizing value.

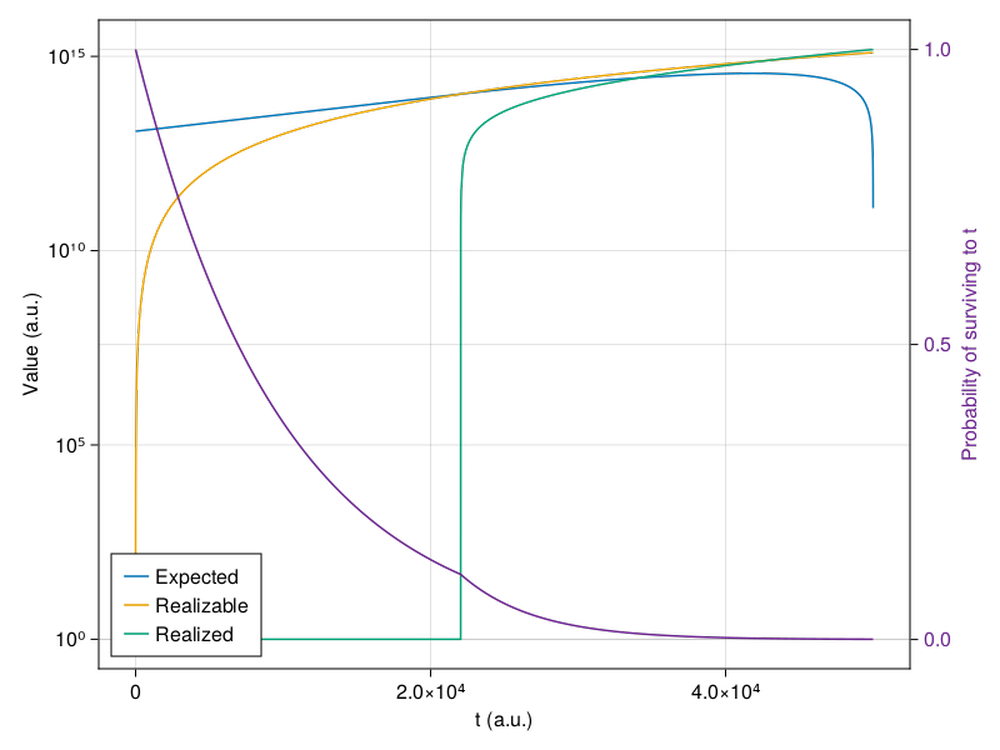

Here’s an example (code at the bottom):

The initial expected value is in fact astronomical, but we’ve maximized it at the cost of back-loading the actual realization of value. By the time it makes sense to enter the “realization” stage, we’re very likely already extinct. The original version of this plot and code had a bug that made it wait too long, making my point look stronger than it was (“almost certainly extinct”) for this choice of model and parameters. ⏎

This isn’t strictly a problem—it’s successful expected utility maximization. There might be an appeal to intuition against expected utility maximization along these lines, although that’s not quite what I’m aiming for. I just think we might expect welfare to be driven down, perhaps below “neutral”, perhaps for a very long time, perhaps with a low chance of reaching payoff, by a maximizer.

using CairoMakie

using OrdinaryDiffEq

function bellman_solve(s, r_0, dr)

t_f = 10*1/r_0 #

v_f = (s*t_f)^3

# minus sign for backwards integration

dvdt(v, p, t) = -((s*(t_f - t))^3 > dr * v ?

(r_0 * v -(s*(t_f - t))^3) : # realizing (st)^3 dt

((r_0 - dr)*v)) # or reducing risk by dr

tspan = (0.0, t_f)

prob = ODEProblem(dvdt, v_f, tspan)

sol = solve(prob, Tsit5(), reltol=1e-12, abstol=1e-12)

return sol

end

function make_plot()

s = 0.1 # Expansion speed

r_0 = 2e-4 # Baseline risk

dr = 1e-4 # Change in risk when "securing"

sol = bellman_solve(s, r_0, dr)

f = Figure(backgroundcolor=:transparent)

ax1 = Axis(f[1, 1],

yscale = log10,

ylabel = "Value (a.u.)",

xlabel = "t (a.u.)",

backgroundcolor=:transparent)

ax2 = Axis(f[1, 1],

yaxisposition = :right,

yticklabelcolor = :darkorchid4,

ylabelcolor = :darkorchid4,

ylabel = "Probability of surviving to t",

backgroundcolor=:transparent)

hidespines!(ax2)

hidexdecorations!(ax2)

t_forward = maximum(sol.t) .- sol.t

realizing = ((s*t_forward).^3 .> dr * sol.u)

t_r =t_forward[findlast(realizing)]

securing = (!).(realizing)

p_alive = exp.(-(r_0 .- dr) .* t_forward) .* securing .+

exp(-(r_0 - dr) * t_r) *

exp.(-r_0 * (t_forward .- t_r)) .* realizing

realized = max.(0, 1/4 * s^3 * ((t_forward).^4 .- t_r^4))

lines!(ax1, maximum(sol.t) .- sol.t, sol.u,

label = "Expected")

lines!(ax1, sol.t, 1 .+ (s*sol.t).^3 / dr,

label = "Realizable")

lines!(ax1, t_forward, 1 .+ realized,

label = "Realized")

lines!(ax2, t_forward, p_alive,

color = :darkorchid4)

axislegend(ax1, position = :lb)

save("p.png", f)

end